Cherry Growing Proved Ripe to Explode 100 Years Ago

ONE FAMILY’S PIONEERING CHERRY STORY

If you want a quick history of the orchard industry on the Door Peninsula, you can stop at the State of Wisconsin Historical Marker a few miles north of Sturgeon Bay along Highway 42 or you can talk to Dale Seaquist. If you’re lucky, you’ve taken one of his step-on bus tours of his family’s orchard in Sister Bay.

The Door Peninsula’s association with fruit growing is certainly far more complex than could be placed on a small sign. There is no mention of Dr. E.M. Thorpe, whose 20 acres of grapes on Strawberry Island near Fish Creek drew first mention in H.R. Holand’s often-referenced history of Door County published in 1917. Who knew? The emergence of grapes on the Peninsula seems a more modern phenomenon as wineries and hardier strains have emerged.

The sign’s location stems from the fact that Joseph Zettel planted his first trees in 1858 in close proximity to the marker’s location. Holand, whose historical accuracy has at times come into question, says the Swiss immigrant’s first trees were planted four years later.

Robert Laurie isn’t mentioned on the sign, but Holand seems to think he was just as significant as Zettel, considering he exhibited 13 different varieties of apples at the first Door County Fair in 1869. Zettel already had 45 acres in apples by this time, making it the largest orchard in the state.

Eventually it produced a yield of 20 varieties that he put on display at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

Suddenly, Door County was being recognized as a prime location for growing fruit, and the other two guys on the sign took notice and set in motion a surge in orchard expansion, especially in one fruit not mentioned to this point.

No fruit is more closely identified with Door County than the cherry, a delicate and tantalizing fruit that presented its own unique challenges to pioneer orchardists but one that proved too intoxicating to resist.

Dale Seaquist with trusty friend among the cherry trees. Contributed photo

Dale Seaquist with trusty friend among the cherry trees. Contributed photo

‘We were certainly one of the first orchards in northern Door County. But we had no marketing plan.’ — Dale Seaquist

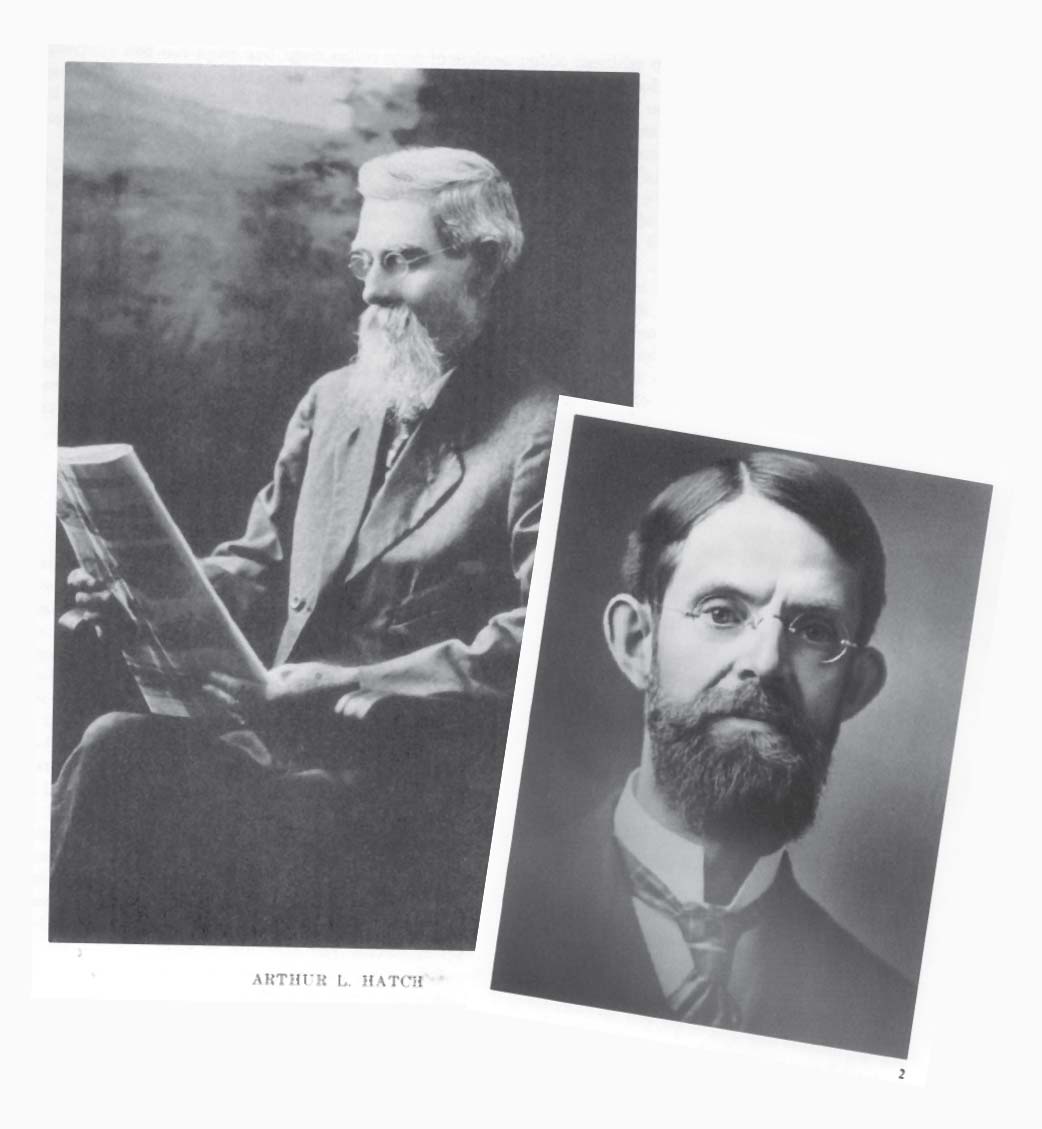

In 1891 A.L. Hatch, a commercial fruit grower from Richland County, and Emmett Goff, professor of horticulture at the University of Wisconsin, came to the Peninsula to investigate.

Zettel told them that conditions were so favorable that he had yet to suffer injury on his fruit from spring frost over his 40 years of growing. Hatch and Goff set out rather small plots on a variety of fruits.

It was their decision in 1896 to concentrate their cherry planting to a particular tart variety known as the Montmorency variety. The rest, they say, is history.

A few other intrepid growers followed suit, playing the waiting game that is necessary between the time a tree is planted and it bears fruit.

These small orchards around Sturgeon Bay eventually began to yield exceptionally promising crops, and with it the legend of Door County cherries began to grow and, with that, the growth of a family business on which that legacy rests heavily to this day. When you sit down with Dale Seaquist in his comfortable home on land rich in his family’s history, he paints a colorful picture of 19th century immigrant life.

“My great-grandfather came over from Sweden to escape religious oppression,” said Dale, now 86 years old. “He wanted to come to America to worship the way he wanted.”

Pioneering fruit growers Arthur Hatch, top, and Emmet Goff, right. Photos courtesy of the Door County Historical Museum

Pioneering fruit growers Arthur Hatch, top, and Emmet Goff, right. Photos courtesy of the Door County Historical Museum

Anders Sjoquist, later changed to Seaquist, eventually settled near Ephraim after bringing the rest of his family over from Sweden. Those strong religious beliefs haven’t been lost on Dale and have been a driving force in the development of a fruit operation that dates back to those first successful harvests by a handful of men who had faith in the area’s unique ability to grow fruit.

It would be the determined pioneering spirit and strong religious faith of Anders and his wife, Sophia, that would carry the family through those early years. A gifted carpenter, Anders took notice of what Goff and Hatch were doing farther south on the Peninsula.

Dale likes to tell of his great-grandfather’s arduous journey through a still-undeveloped land to scout out the roots of this budding industry. Seaquist’s first commercial orchard was planted in 1911, and its growth and development would fall on Ander and Sophia’s son Carl Robert and his son John, Dale’s father. Like those early growers, it was situated right behind Carl Robert’s home.

“We were certainly one of the first orchards in northern Door County,” said Dale. “But we had no marketing plan.”

With such a short harvesting season and a perishable fruit, early growers were stressed to find markets, and for the Seaquists it meant running boatloads of cherries across Green Bay to Michigan.

With so many orchards going in, it was only a matter of time before they matured and the market would be flooded with cherries without the transportation system needed to get them to farflung markets. A lot of fruit spoiled before it could be shipped and sold.

“Housewives had already been canning fruit and making jam and jelly at home for years,” wrote John Enigl in a story that appeared in the Door County Almanak. “It only took the development of machines to do the job in a factory to permit the preservation of fruit commercially.”

This summer marks the 100th anniversary of the creation of the Fruit Growers Canning Company. It was an offshoot of the Door County Fruit Growers Union that in itself was a pioneering effort in agriculture cooperatives.

As the cherry season of 1919 approached, the Door County News reported on a visit to Sturgeon Bay by Chicago merchandise broker Warren Jones.

After visiting the new canning factory in Sturgeon Bay, Jones immediately realized the significance of the facility and could see the impact it would have in ultimately making Door County “Cherryland USA.”

Jim Seaquist in an apple orchard. Contributed photo.

Jim Seaquist in an apple orchard. Contributed photo.

“People here do not realize what they have in the cherry cannery,” he told the paper. “Why, this is the largest factory in the United States, double the capacity of any other single factory. Where the next largest only operates four machines, this one is operating nine.”

Jones seemed to be equally impressed with the quality of the fruit that came to the factory in larger numbers than expected that first season a century ago.

“This is a fine thing for growers, for if they did not have the factory to can the fruit that is too ripe for shipment a long distance, they would suffer a loss,” explained Jones.

But as important as canning was in supporting an ever-growing number of growers that Dale said would eventually number well into the hundreds, one other key component helped the early development of the cherry industry.

With the success of University of Wisconsin agricultural research stations around the state, the growing number orchards prompted cries for a similar facility on the peninsula with its unique growing conditions.

It was also 100 years ago that the first headlines appeared in local papers about a need for a station. Just three years later in 1922, the station opened a few miles north of Sturgeon Bay on what was a small dairy farm.

While a connection to Professor Goff certainly helped in the decision, former station superintendent Richard Weidner said the county was an interesting proving ground, being far different from other parts of the state.

“This was not an area for annual plantings but rather perennial with its thin soil and propensity to drought,” said Weidner. “The tree is adaptable, winter hardy.”

Weidner could see why early pioneers like the Seaquists took to planting orchards.

“It was venture capitalism at its best,” he said. “There was a lot of available land that was poor for other agriculture, and trees were cheap.”

It sparks a reminder to when Dale said those first trees his family planted came at a cost of 6 cents apiece.

But the research station was more important in providing the ammunition the growers needed to fend off disease and pests.

Like a hospital opening in a growing town, the station has been there to tend to the health issues of a fruit that Weidner said has always been “prone to injury.”

It’s a delicate fruit in a delicate market that makes what the Seaquists have accomplished all the more impressive.

The family is moving into the sixth generation centered on that same property Anders first settled. The number of cherry growers has declined significantly since the glory days in the middle of the 20th Century.

Dale’s son Jim now leads the company along with more than 12 family members working together to make all of this go.

In helping to preserve Door County’s cherry legacy, Seaquist has absorbed other orchards into its operations and now has 150,000 trees on 1,200 acres, some apple but mostly cherry, making it by far the largest cherry orchard in Wisconsin.

“We have all been blessed to have this opportunity to contribute to the success of this farm,” said Jim. “We certainly don’t have to go to Las Vegas,” he adds, referring to the unpredictability of what Mother Nature might inflict on a particular year’s crop.

But the family has forged on with an operation that encompasses all aspects of fruit growing, from the planting, harvesting, processing, canning and even selling product in its farm market.

“We’ve been lucky to have a family that works together well,” said Jim.

Certainly, Anders and Sophia would be proud..